- Home

- James Longenbach

How Poems Get Made

How Poems Get Made Read online

JAMES LONGENBACH

_____________

HOW POEMS

GET MADE

______________________________

_____________

To Russ McDonald

CONTENTS

Preface

I.

Diction

II.

Syntax

III.

Voice

IV.

Figure

V.

Rhythm

VI.

Echo

VII.

Image

VIII.

Repetition

IX.

Song

X.

Tone

XI.

Prose

XII.

Poetry

Acknowledgments

Further Reading

Bibliography

Credits

Index

PREFACE

The impulse to be lyrical is driven by the need to feel unconstrained by ourselves. As poems have testified for centuries, we become lyrical when we suffer, when we love. But like poems themselves, we exist because of constraints—cultural and linguistic ways of organizing experience that allow us to know who we are. Why, when we’re driven to be lyrical, are we gratified by the repetition of words, rhythms, and phrases? Why, having experienced the pleasure of a lyric poem once, do we want to experience it again? Why, when we’re in love, can the repetition of an experience feel more fulfilling than the discovery?

This book describes how English-language poems get made from the most fundamental elements of their medium: the diction, syntax, figures, and rhythms of the English language itself. Because of a poet’s organization of these elements, some poems may also be distinguished by qualities we call (more metaphorically) voice, image, or tone. These same qualities may distinguish prose, but through the simultaneous repetition and disruption of patterns, lyric poems aspire (sometimes literally, more often metaphorically) to the condition of song. Nobody rereads Keats’s ode “To Autumn” to be reminded that in September leaves turn colors and fall from the trees; even if we know the poem by heart, we savor our experience of the poem’s language as it unfolds in time, luring us forward.

There is of course a great deal to be said about diction, syntax, figuration, rhythm, or tone, and my goal is to offer succinct accounts of the poetic procedures with which any writer or reader would want to be intimate. Aspects of poems not registered in my chapter titles (such as line, rhyme, punctuation, disjunction) are treated along the way, each chapter building on the one preceding it, the whole book moving toward an ever-widening account of how poems are structured not as static vessels for meaning but as temporal events. While our first encounter with anything from a poem to a parking ticket might be revelatory, reading the same paragraph from a ticket as many times as one has read the ode “To Autumn” would probably not be satisfying—except if the paragraph’s language enacts an emergence, a coming into being, that feels infinitely repeatable, richer over time.

Among the poets whose procedures I’ll describe are Blake, Crane, Dickinson, Donne, Keats, Lawrence, Moore, Shakespeare, and Wyatt, along with a small array of contemporaries. Because they hold our attention as repeatable events, the best-known poems may seem wonderfully strange, especially after long acquaintance. And because their medium, the language we speak every day, is itself so familiar, we may experience the pleasure of what I’ll call lyric knowledge—the eager rediscovery of what we already know—not only when we least expect it but when we expect it too well. A poem gets made not only in the act of composition but every time we read it again.

HOW POEMS

GET MADE

I

DICTION

The medium of Giorgione’s “Tempest” is “oil on canvas”; the medium of Robert Rauschenberg’s “Bed” is “oil and pencil on pillow, quilt, and sheet.” Very few people handle oil paint as provocatively as Rauschenberg, but lots of people sleep on sheets. Those people may also draw a little, they may have a fine sense of color, but they respect the transaction between artist and medium that a particular work of art not only records but embodies. Sometimes, however, when the sheer otherness of the medium is foregrounded at the expense of a conventional signal of the artist’s mind at work, people don’t respect the transaction, in part because the artist doesn’t covet such respect: how can art be something made of a bed sheet?

How can art be something made of words? Unlike the media most commonly associated with visual or musical artistry, words are harnessed by most people during almost every waking moment of their lives; they’re more like sheets than like oil paint or the notes of the scale. Even small children are skilled manipulators of language, capable of detecting and repeating the most subtle nuances of tone. But children don’t write the poems of Shakespeare or the novels of Henry James, and neither do most adults. We may sustain an easy mastery of language in our daily lives, but once we engage language as an artistic medium, that mastery is never secure: our relationship to language is constantly changing as we discover aspects of the medium that not only our prior failures but, more potently, our prior successes had occluded.

My medium is not language at large but the English language. When I was young I took this for granted, but over the years I’ve become increasingly conscious of the qualities shared by sentences because they’re written in English, rather than German or French. The very word medium, derived from Latin, did not enter the English language until the Renaissance, when it referred to something that acts as an intermediary, like a piece of money or a messenger, and it was not until the nineteenth century that the word began to be used to describe the stuff from which art is made: the artistic medium enables a transaction between the artist and the world, and, over time, the history of those transactions has become inextricable from the medium itself. It’s not coincidental that it was also in the nineteenth century that the word medium was first used to describe a person who conducts a séance, a person who exists simultaneously in the worlds of the living and the dead.

Every language has different registers of diction, but English comes by those registers in a particular way, one that reflects the entire history of the language. Old English, the language of the eighth- or ninth-century poem we call “The Seafarer,” now looks and sounds to us like a foreign language, close to the German from which it was derived: with some study, one can see that the Old English line “bitre brēostceare gebiden hæbbe” means “bitter breast-cares abided have” or “I have abided bitter breast-cares.” The language of Chaucer’s fourteenth-century Canterbury Tales, or what we call Middle English, feels less strange, in part because its syntax now relies largely on word order rather than on word endings: “Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages” or “then people long to go on pilgrimages.” And the Modern English of the Renaissance we can read easily, because it is the language we speak today, even though the language has continued to evolve.

Let me not to the marriage of true minds

Admit impediments.

Many complicated factors determined this evolution, but one of the most important was the Norman invasion of England in 1066. Once Norman French became the language of the English court, a new vocabulary of words derived from Latin began to migrate into Germanic English. The Old English poet could abide breast-cares, but he could not go on a pilgrimage or suffer impediments or employ a medium; those Latinate words were not available to him. Even today, we raise pigs and cows (from German, via Old English) but eat pork and beef (from Latin, via French), because after the Norman conquest the peasants who raised animals generally spoke English while the noblemen who ate them spoke French. In the Renaissance, Latinate words were increas

ingly imported not only from French but directly from Latin itself, bequeathing to us an even wider menu of discriminations: fear (from German), terror (from French), trepidation (from Latin). English remains at its root a Germanic language, but around 70% of its vocabulary comes from non-English sources, and while the bulk of these borrowings had occurred by Shakespeare’s lifetime, the language continues to expand, resulting in the variety of World Englishes spoken today.

Speakers of English may or may not be aware that their language is by its nature at odds with itself, but even the simplest deployment of English as an artistic medium depends on the juxtaposition of words with etymologically distant roots—words that sound almost as different from each other as do words from German and French. Chaucer’s line “Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages” mixes Germanic and Latinate diction strategically (the plain folk playing off the fancy pilgrimages), and Shakespeare’s sentence “Let me not to the marriage of true minds / Admit impediments” does so more intricately, the Germanic monosyllables let, true, and minds consorting with the Latinate marriage, admit, and impediments to create the polyglot texture that speakers of English have come to recognize as the sound of eloquence itself. The extravagantly polyglot texture of Jean Toomer (“give virgin lips to cornfield concubines”) or John Ashbery (“traditional surprise banquet of braised goat”) feels idiosyncratic because it is also conventional, driven by the authors’ intimacy with their expanding medium.

It’s possible to suppress that texture, though not completely. In this passage from Ulysses, James Joyce writes as if Modern English were an almost exclusively Germanic language, giving priority to Germanic monosyllables and organizing the syntax as if English were still a highly inflected language, in which sense is less dependent on word order.

Before born babe bliss had. Within womb won he worship.

And in this passage, Joyce writes English as if it were an almost exclusively Latinate language, frontloading Latinate vocabulary and weeding out as many Germanic words as possible.

Universally that person’s acumen is esteemed very little perceptive concerning whatsoever matters are being held as most profitably by mortals with sapience endowed.

But these feats of stylistic virtuosity sound more like the resuscitation of a dead language than the active deployment of a living one; it’s difficult to speak English so single-mindedly. In contrast, Shakespeare’s language feels fully alive in Sonnet 116, and yet its drama depends on the strategic juxtaposition of a Germanic phrase (“true minds”) with a highly Latinate phrase that a speaker of English might never say (“admit impediments”), just as that speaker probably wouldn’t say “babe bliss had” or “with sapience endowed.” We don’t speak of the cow who jumps over the moon as “translunar,” though we could, and it is at such junctures that our language begins to function as an artistic medium: nothing is automatically a medium, though anything could be.

A medium, says the psychoanalyst Marian Milner in On Not Being Able to Paint, is a little bit of the world outside the self that, unlike the resolutely stubborn world at large, may be malleable, subject to the will while continuing to maintain its own character. The medium might be chalk, which cannot be made to produce the effects of watercolor. It might be a copperplate coated with a thin layer of silver and exposed to light. It might be a rosebush, pruned and fertilized into copious bloom, or an egg, exquisitely poached. In the realm of psychoanalysis, the medium is the analyst, a person who can be counted on to respond to the wishes of the analysand without needing to assert his own, as any person in an ordinary human relationship inevitably would.

But neither the analysand nor the artist may indulge in any infantile wish of dominating the medium completely. A visitor to Picasso’s studio once recalled that, after squeezing out the paint on his palette, Picasso addressed it in Spanish, saying, “You are shit. You are nothing.” Then he addressed the paint in French, saying, “You are beautiful. You are so fine.” This conflict of attitudes (in this case so contentious that two languages are required to enact it) seems crucial. For if the artist loves the medium enough to submit himself to its actual qualities, resisting exaggerated notions of what the medium can do at his beck and call, then the result will likely be something recognizable as a work of art, a transaction between the mind and the world that is played out in the material reality of the medium.

The satisfaction of art may consequently be found in a poached egg or a child’s drawing, but I suspect that we’re most often moved to call a work of art great when we feel the full capacity of the medium at play, nothing suppressed, as if the artist’s command of the medium and the long history of the medium’s deployment by previous artists were coterminous—which, in a sense, they are.

It is for Shakespeare’s power of constitutive speech quite as if he had swum into our ken with it from another planet, gathering it up there, in its wealth, as something antecedent to the occasion and the need, and if possible quite in excess of them; something that was to make of our poor world a great flat table for receiving the glitter and clink of outpoured treasure.

While invoking Keats’s sonnet “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer” (“Then felt I like some watcher of the skies / When a new planet swims into his ken”), this sentence by Henry James enacts the Shakespearean work it describes, overwhelming us with a feeling of unstoppable excess. The juxtaposition of Germanic bluntness and Latinate elaboration is immediately as apparent as it is in Shakespeare (“constitutive speech,” “something antecedent,” “occasion and the need,” “quite in excess,” “great flat table”), and, at the end of the sentence, as the last clause walks effortlessly to the finish line, the strategy is raised to virtuosic heights: “the glitter and clink of outpoured treasure.”

This sentence sounds like James, but by performing the action it describes, the sentence also implies that linguistic virtuosity in Modern English is in some indelible way Shakespearean, and the implication, though easily abused, is not merely sentimental. Shakespeare was a powerful writer who in his lifetime was poised at exactly the right moment to take advantage of the medium that the English language had only recently become. He could reach for effects that had been unavailable to the poets of both “The Seafarer” and The Canterbury Tales, and because of the particular power with which he did so, poems we think of as great, poems that harness the full capacity of the medium, often tend to sound to us Shakespearean. But what we are really hearing in such poems is the medium at work; what we are hearing is the efforts of a great variety of writers to reach for the effects that Modern English most vigorously enables.

The Germanic and Latinate aspects of English are themselves hardly monolithic, but English words derived from German may often seem vulgar or plain; English words derived from Latin may often seem officious or magical. Yet the particular way in which a lyric poem engineers the juxtaposition of such words may alter those associations instantly, if not permanently, making the bluntest monosyllables seem magical. The final sentence of Marianne Moore’s “My Apish Cousins” (later called “The Monkeys”) is an effortlessly Jamesian extravaganza spoken by a cat, who is enraged by people who make the experience of art seem unavailable to the simpler mammals.

I shall never forget—that Gilgamesh among

the hairy carnivora—that cat with the

wedge-shaped, slate-gray marks on its forelegs and the

resolute tail,

astringently remarking: “They have imposed on us with

their pale

half fledged protestations, trembling about

in inarticulate frenzy, saying

it is not for all of us to understand art, finding it

all so difficult, examining the thing

as if it were something inconceivably arcanic, as

symmetrically frigid as something carved out of chrysopras

or marble—strict with tension, malignant

in its power over us and deeper

than the sea when it proffers flatt

ery in exchange

for hemp,

rye, flax, horses, platinum, timber and fur.”

Until the final line, almost all the nouns in this sentence have been derived from Latin (protestations, frenzy, tension, power, flattery, exchange) and so have most of the modifiers (inarticulate, difficult, inconceivably, symmetrically, frigid, malignant). Of the verbs driving us through this exfoliation of dependent clauses, luring us through a verbal texture that is almost overwhelmingly rich but never grammatically unclear, about half of them are Latinate (impose, examine, proffer). When we are finally thrown into the list of nouns with which the sentence concludes, the mostly Germanic monosyllables seem to rise magically, extruded from the language preceding them: “hemp, / rye, flax, horses, platinum, timber and fur.”

Moore’s diction is not showy or contrived; she is acutely conscious of inherited gradations within the vocabulary we harness in every sentence we speak. So while the final sentence of “My Apish Cousins” is a theatrical manipulation of those gradations, it sounds not like a reduction of the medium (“babe bliss had”) but like an inhabitation of the medium (“the glitter and clink of outpoured treasure”). After all, “My Apish Cousins” asks us to attend not to what is fancy or artificial but to what is fundamental and plain—hemp, rye, flax. And yet the poem also suggests that we recover our sense of wonder in the face of plain things only through highly intricate means. For while six of those final nouns could readily have been harnessed by the Old English poet of “The Seafarer” (hemp, rye, flax, horses, timber, fur), one of them stands out as egregiously Latinate: platinum was first discovered in the new world by the Spanish, who thought it was an inferior form of silver; they called it platina, a diminutive form of the word plata, meaning silver. Is platinum a false kind of silver or a thing unto itself, like hemp or flax?

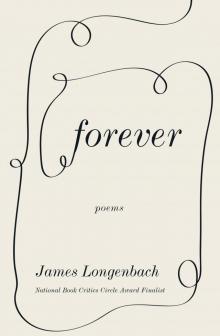

Forever

Forever How Poems Get Made

How Poems Get Made